You're browsing the web, and a page loads instantly. What you might not realize is that the image you're seeing, the stylesheet that styles the page, or the script that makes it interactive very likely didn't come directly from the original website's server. It came from a middleman a caching proxy or a Content Delivery Network (CDN) like Cloudflare or Akamai.

This behind-the-scenes infrastructure is what makes the modern web fast and scalable. But it also introduces a layer of complexity: how does the system communicate that a response has been modified or served from a different source than the origin?

If you've ever browsed the web or worked with APIs, you might have encountered various HTTP status codes. Most people are familiar with common ones like 200 OK or 404 Not Found, but what about less common ones like 203 Non-Authoritative Information? In this blog post, we'll explore what the 203 status code means, when it appears, and why it matters especially for developers and API users who want to understand the nuances of web communication.

This is the niche job of one of HTTP's most obscure and rarely seen status codes: 203 Non-Authoritative Information.

This status code is the server's (or more accurately, the proxy's) way of saying, "Hey, I'm giving you what you asked for, but you should know that I'm not the original source, and I might have made some changes to it on the way."

It's the digital equivalent of getting a memo from your boss's assistant. The information is valid and comes from the right place, but it's been paraphrased or summarized, not a direct, verbatim quote from the boss themselves.

If you're a developer working with proxies, CDNs, or API gateways, understanding this code is a key to deep HTTP mastery.

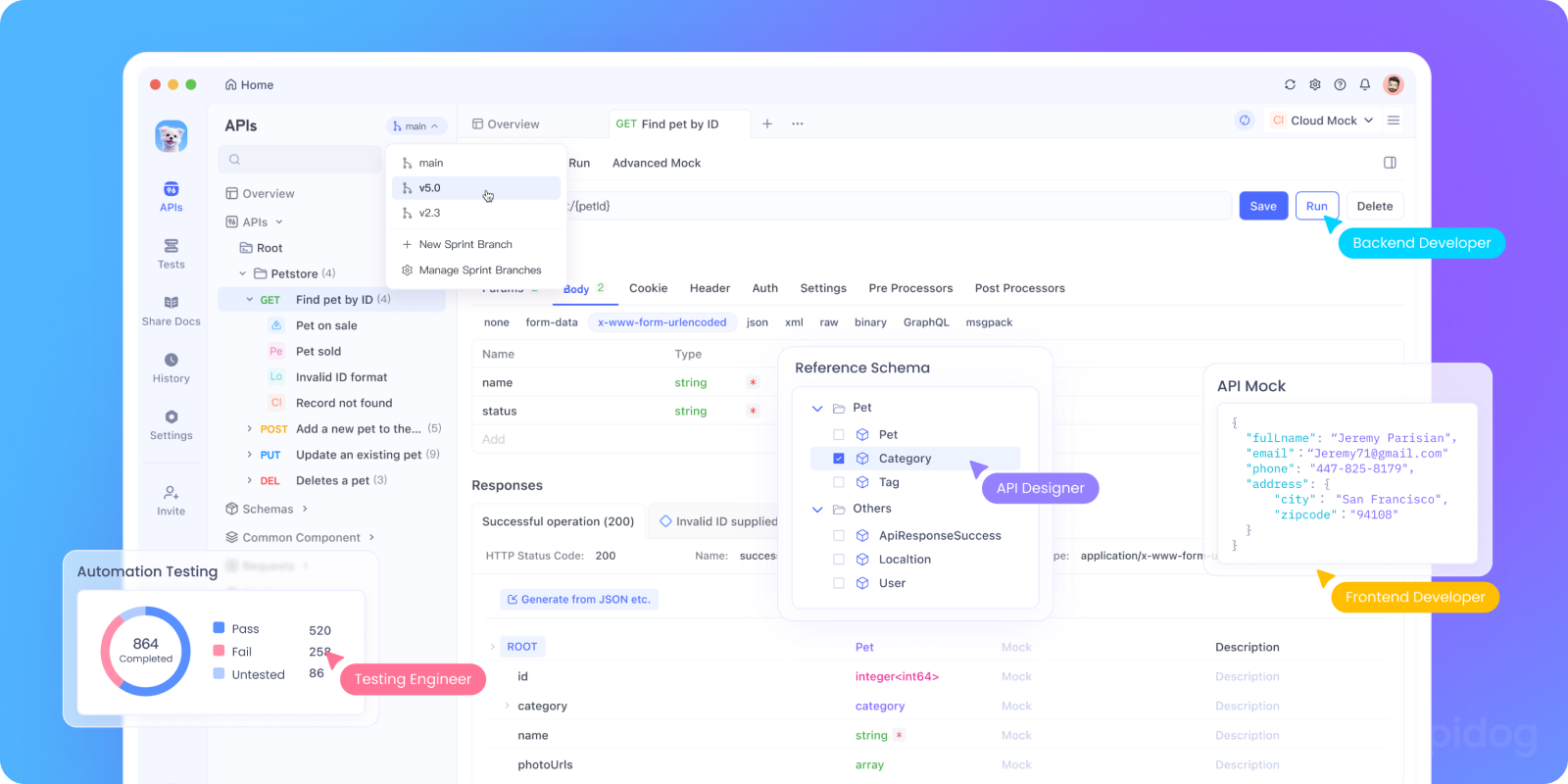

And before we dive into the specifics, if you're building or testing APIs that sit behind gateways and proxies, you need a tool that gives you deep visibility into the entire HTTP conversation. Download Apidog for free; it's an all-in-one API platform that allows you to inspect every header and status code, helping you debug complex interactions involving intermediaries.

Now, let’s break down everything you need to know about 203 Non-Authoritative Information in plain terms.

The Cast of Characters in a Web Request

To understand 203, we need to understand the typical journey of a web request, which is rarely a simple two-way conversation.

- The Client (You): Your web browser or application is making a request.

- The Origin Server: The ultimate source of the truth, the server that hosts the website or API.

- The Intermediary (The Middleman): This can be several things:

- A Reverse Proxy / Load Balancer: Sits in front of origin servers to distribute traffic and improve performance.

- A CDN (Content Delivery Network): A globally distributed network of proxies that cache content close to users.

- An API Gateway: A single entry point for APIs that can handle authentication, rate limiting, and request transformation.

The 203 status code is generated by this intermediary, not the origin server.

What Does HTTP 203 Non-Authoritative Information Mean?

The official definition (from RFC 7231) states that a 203 response means:

The request was successful but the enclosed payload has been modified from that of the origin server's 200 OK response by a transforming proxy.

Let's break down the key phrases:

- "The request was successful...": This is a success code, part of the 2xx family. The client did get a valid response.

- "...modified from that of the origin server's 200 OK response...": This is the core of the message. The response body the client received is not exactly what the origin server would have sent.

- "...by a transforming proxy.": This is the actor responsible for the change. A "transforming proxy" is any intermediary that alters the response.

In essence, the intermediary is being transparent. It's saying, "I'm not the origin server, and I've done something to this response before handing it to you."

In plain terms, a 203 response indicates that the server successfully processed the request, similar to the 200 OK status. However, the information returned is coming from a third party or some other source that the server trusts but doesn't officially control. Therefore, the information may have been modified or augmented by the proxy or gateway before sending it to the client.

To put it simply: The response is good, but the data may not be exactly what the original, authoritative server has think of it like getting a filtered or enhanced version of the original content.

Why Does the 203 Status Code Exist?

You might wonder, why have this status code at all? Why not just send 200 OK all the time?

The reason lies in transparency and control. Imagine a caching proxy server or a content delivery network (CDN). These intermediaries often serve copies of web content to reduce load on the main server and improve speed. Sometimes, they modify or add information before passing it along.

The reason 203 exists is to help differentiate between original and modified responses. Sometimes proxies or middleware alter responses for example:

- A caching proxy injecting headers.

- A translation service rewriting text.

- A content filter adding or stripping information.

Using 203 tells the client, "Hey, this is the data you asked for, but note it might have been altered or enhanced by an intermediary."

This transparency is particularly helpful in debugging, logging, or when strict data provenance matters for example, in API responses where the source of data affects trust or compliance.

Key Characteristics of 203

Here’s what makes 203 unique:

- Success implied: The request worked.

- Modified response: Content may not match the exact origin.

- Intermediaries involved: Often triggered by proxies, caches, or filters.

- Rare in practice: Many developers never encounter it, but it’s still part of the HTTP/1.1 spec.

Why Would a Proxy Modify a Response? Common Use Cases

An intermediary doesn't alter responses for no reason. Here are the most common scenarios where a 203 might be used:

- Adding or Modifying Headers: This is the most common use. A CDN might add a

Viaheader to show it handled the request or aX-Cacheheader to indicate if it was a cache HIT or MISS. An API gateway might inject aRateLimit-Limitheader. - Content Transformation: A proxy might downgrade images to a lower quality to save bandwidth on mobile networks. It might minify JavaScript or CSS files to make them smaller and faster to load.

- Annotation: A security scanner proxy might add annotations to the HTML body indicating that links have been checked for safety.

- Caching: While a cached response would typically return a

200or304, a proxy might use203if it applies some logic to the cached content before serving it.

The Mechanics: How a 203 Response is Generated

Let's walk through a hypothetical example involving an API gateway.

- Client Request: A client sends a request to an API.

GET /api/users/me HTTP/1.1Host: api.example.comAuthorization: Bearer <token>

2. Gateway Processing: The request hits an API gateway first. The gateway:

- Validates the JWT token.

- Checks rate limits.

- Forwards the request to the actual backend service (the origin server).

3. Origin Response: The backend service processes the request and responds.

HTTP/1.1 200 OKContent-Type: application/jsonServer: Origin-Server/1.0

{"id": 123, "username": "johndoe", "email": "john@example.com"}

4. Gateway Transformation: The gateway receives this response. Before sending it to the client, it decides to add some helpful information.

- It injects a new header:

X-RateLimit-Limit: 1000 - It adds a

Viaheader to indicate it processed the request.

5. Gateway's 203 Response to Client: The gateway determines that it has modified the response enough to warrant a 203 status. It sends this to the client:

HTTP/1.1 203 Non-Authoritative InformationContent-Type: application/jsonServer: Origin-Server/1.0Via: 1.1 api-gatewayX-RateLimit-Limit: 1000

{"id": 123, "username": "johndoe", "email": "john@example.com"}

Notice the body is the same, but the headers are different, and the status code has changed from 200 to 203.

Handling 203 Responses in API Development

If you're building or consuming APIs, understanding and handling the 203 status code can help you build more reliable and transparent systems.

Here’s what you should consider:

- Client Awareness: Your client application should be aware that 203 means the received data might be modified and act accordingly if data authenticity is critical.

- Logging & Monitoring: Track 203 responses distinctly to investigate possible data modification by intermediaries.

- Error Handling: Handle 203 status similarly to 200 OK but with added caution about data source verification.

- Documentation: Clearly document when your API might return 203 and what it means for the client.

203 vs. 200 OK: A Crucial Distinction

This is the most important comparison. Why use 203 instead of just passing through the origin's 200?

200 OKfrom a proxy means: "Here is the response. It is exactly what the origin server sent me, and I've done nothing to it (besides maybe adding some of my own headers)."203 Non-Authoritative Informationmeans: "Here is the response. It is based on what the origin server sent, but I have modified it in a way that changes its meaning or content. Tread carefully."

The 203 is a signal of transparency and a warning to the client that the response is not a pristine, first-hand copy from the source.

The Reality: Why You Almost Never See 203

Despite being defined in the HTTP standard, the 203 status code is exceedingly rare in the wild. Here’s why:

- Lack of Widespread Adoption: Many proxy and CDN developers simply don't implement it. The prevailing attitude is that adding headers isn't a significant enough transformation to warrant changing the status code.

- Risk of Breaking Clients: A poorly written client might handle a

200successfully but choke on a203, even though they are both success codes. To avoid this risk, intermediaries almost always just pass through the origin's status code. - Headers are Considered "Safe": The common interpretation among proxy developers is that adding informational headers (like

Via,X-Cache,Rate-Limitheaders) does not constitute a modification of the "payload" or "information" that warrants a203. They see the "information" as the body, not the headers. - It's Often Unnecessary: The intermediary can simply use other headers to convey information about itself. The

Viaheader itself is enough to tell a client that a proxy was involved, without needing to change the status code.

When Might You Actually See a 203?

While rare, it's not extinct. You might encounter it in:

- Highly Custom API Gateways: A company with a custom-built gateway might choose to implement

203for any modification, strictly adhering to the RFC. - Academic or Research Proxies: Projects focused on the intricacies of HTTP might use it correctly.

- Security or Filtering Proxies: If a proxy actively strips out or modifies content in the response body for security reasons (e.g., removing malicious scripts), a

203would be a very appropriate signal.

203 in REST APIs vs GraphQL APIs

- REST APIs: 203 fits naturally, since REST relies heavily on HTTP semantics.

- GraphQL APIs: Less common, because GraphQL usually controls the response format directly, but intermediaries could still trigger 203.

Testing and Debugging with Apidog

Working with various HTTP status codes, especially uncommon ones like 203, requires smart tools. Whether you're building a proxy that might generate 203 or consuming an API that does, you need a tool that can capture and make sense of these nuances. Apidog is perfect for this.

With Apidog, you can:

- Capture Full Responses: Inspect not just the status code but every single header, allowing you to spot the modifications that might have triggered a

203. - Compare Requests: Easily replay a request through different paths (e.g., directly to the origin vs. through a gateway) and use Apidog's comparison features to see the differences in responses.

- Test Client Resilience: If you're building a client, you can use Apidog's mock server to simulate a

203response and ensure your application handles it correctly without breaking. - Document Behavior: Document the expected behavior of your APIs and proxies, including potential status codes like

203, right within your Apidog workspace.

This deep level of inspection is crucial for understanding the complex interactions that happen between your client and your origin server. By integrating Apidog into your workflow, you can save time and reduce confusion when working with nuanced HTTP statuses.

Apidog vs Other API Tools for 203 Testing

- Postman: Great for manual testing, but mocking proxy behaviors for 203 can be tricky.

- Swagger UI: Useful for docs, but doesn’t simulate modified responses.

- Apidog: Combines design, mock servers, testing, and documentation making it easier to explore niche codes like 203 Non-Authoritative Information.

Best Practices: If You're Implementing a Proxy

If you are building a transforming proxy and want to adhere strictly to the HTTP spec, consider these guidelines:

- Use

203for Body Modifications: If you alter the response body (e.g., image transcoding, HTML annotation), a203is highly appropriate. - Be Conservative with Headers: The industry standard is to not use

203for header additions alone. Using headers likeViais sufficient. - Ensure Client Compatibility: If you do use

203, test thoroughly with all your clients to ensure they treat it as a success code like200.

Common Misconceptions About 203 Status Code

Let's clear up a few myths:

- 203 means an error: Not true. 203 means success, but the response is from a source that may be modified.

- 203 responses are rare and don't matter: They are less common than 200 but useful in certain network architectures.

- Clients should treat 203 as 200: Clients can treat it like 200, but ideally, they should be aware of the data origin for trust decisions.

Conclusion: A Code of Transparency

The HTTP 203 Non-Authoritative Information status code, while largely a historical curiosity in today's web, represents an important principle: transparency in communication.

It's a mechanism for the often-invisible intermediaries of the web to be honest about their role. They are not the origin of truth, and if they've changed something, they should say so.

As a developer, understanding 203 helps you:

- Debug odd response behaviors.

- Build more resilient clients.

- Communicate API expectations clearly.

This helps clients make informed decisions about data credibility and improves debugging in complex network ecosystems. For most developers, you will likely never need to actively use or handle this status code. But understanding its purpose gives you a deeper appreciation for the complexities of HTTP and the layered architecture of the internet. It reminds us that a response is not just a body and a status; it's a story of the journey a request took, and the 203 status code is one of the ways that story can be told.

For the vast majority of your API work, you'll be dealing with 200, 201, 400, and 500 status codes. If you want to explore status codes like 203 more effectively or test your APIs with detailed insights, don’t forget to download Apidog for free. Apidog simplifies API testing and documentation, supporting a wide range of HTTP status codes to make your developer experience smoother. And for designing, testing, and documenting those APIs, a tool like Apidog provides the modern, all-in-one platform you need to ensure your APIs are robust, reliable, and a pleasure to use, no matter how many intermediaries are involved in the chain.