Testing is a critical part of software development. It doesn't matter whether you build a small web application or a large distributed system, understanding the types of testing helps ensure that your code is reliable, maintainable, and meets both functional and non-functional requirements. In this article, we’ll explore the most important testing types, when to use them, and how tools (like Apidog) can help, especially when testing APIs.

What Is Software Testing and Why It Matters

Software testing is the practice of evaluating applications to identify defects, verify correct behavior, and ensure quality before users ever interact with the software. Proper testing can catch bugs early, reduce risk, improve reliability, and ultimately save cost and time. But because exhaustive testing is practically impossible, it’s vital to choose the right testing strategy and combine different types to balance coverage and resources.

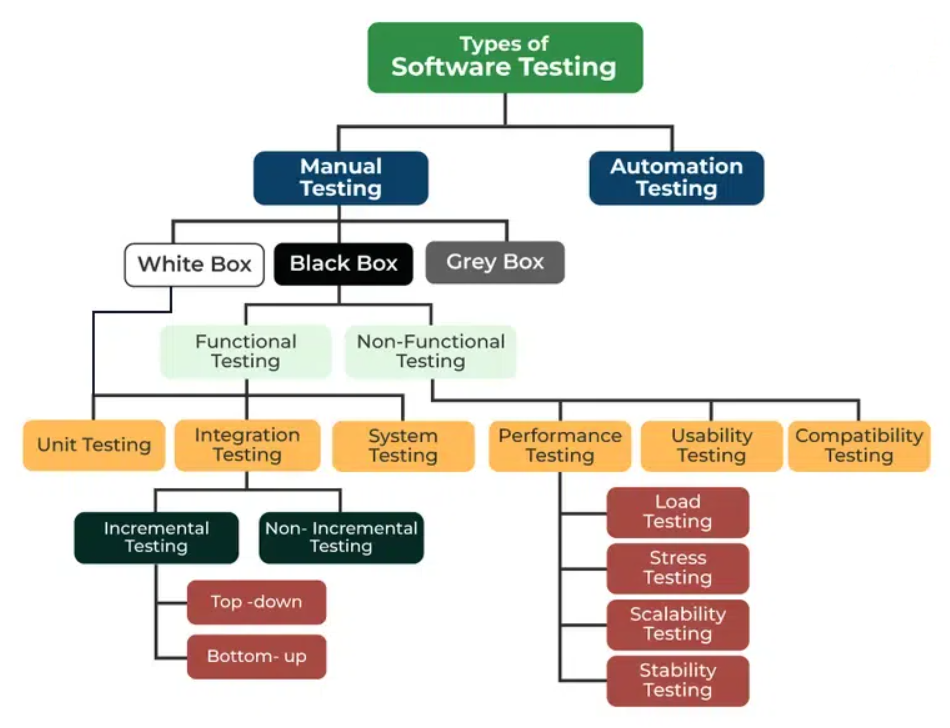

At a high level, testing can be grouped into Functional Testing — checking that the system does what it should — and Non-Functional Testing — evaluating how well the system performs (speed, security, usability, etc.).

Within those groups, many specific types — from “unit testing” to “performance testing” — serve different purposes depending on the stage and scope of development.

Core Types of Software Testing

1. Unit Testing

Unit testing is the most granular level of testing: it tests individual components, functions, or methods in isolation, without external dependencies.

- Purpose: Verify that each small “unit” of code behaves correctly.

- When: Usually during development, by developers.

- Advantages: Fast to run, easy to automate, catches bugs early — which makes code safer when refactoring or building on top of it.

Unit tests are typically automated, and you can (and should) run them many times during development for quick feedback.

2. Integration Testing

Once individual units work correctly, integration testing checks whether they work together properly. It verifies interactions between modules, components, databases, APIs, or services.

- Purpose: Detect interface, data-flow, or interaction issues that unit tests might miss.

- When: After unit tests — often before the system is fully assembled.

- Benefits: Helps ensure modules communicate correctly, data flows as expected, and combined behavior aligns with design.

Because integration tests involve more parts of the system, they may be more costly to set up or run than unit tests — but they are crucial for catching broader issues early.

3. System Testing

System testing treats the application as a whole. The goal is to test a fully integrated system to ensure it meets both functional and non-functional requirements.

- Purpose: Confirm that the complete system works as expected in an environment similar to production.

- What It Covers: Functional correctness, business logic, performance basics, and sometimes non-functional aspects like usability or security (depending on the scope).

- When: After integration testing, often by QA teams or testers who may not need to know internal code.

System testing offers a final verification before acceptance testing or release.

4. Acceptance Testing

Acceptance testing — often called User Acceptance Testing (UAT) — tests whether the system meets the requirements and expectations of stakeholders or end users. This normally happens toward the end of development, before release.

- Purpose: Ensure that the application delivers the promised functionality and behavior from a user or business perspective.

- Who does it: End-users, stakeholders, or QA teams simulating real-user scenarios.

- Outcome: Determines whether the product is acceptable for release or requires modifications.

5. Regression Testing

Regression testing involves re-running existing tests after changes — like bug fixes or new feature implementations — to ensure that existing functionality has not been negatively impacted.

- When: After any change (code, configuration, dependencies) that might affect existing behavior.

- Benefit: Prevents “regressions” — unintended bugs introduced by updates.

6. Performance & Load Testing

Under the umbrella of non-functional testing, performance testing (sometimes split into load, stress, volume, endurance testing) measures how the system behaves under various workloads. This includes response times, concurrency handling, scalability, and stability over time.

- Purpose: Ensure that the system meets performance requirements (speed, scalability, stress-handling) under realistic or extreme conditions.

- When: During QA or before release — especially for services expected to handle many users or high load.

7. Security Testing

Security testing aims to identify vulnerabilities, weaknesses, and potential attack vectors — ensuring that the system is resilient to unauthorized access, data leaks, and malicious behavior. While not always categorized as a distinct “level,” it's critical for any system handling sensitive data or exposed publicly. Security testing often includes penetration testing, access-control testing, and vulnerability scanning.

8. Usability, Compatibility, and Other Non-Functional Testing

Beyond performance and security, software may be tested for usability (user-friendliness), accessibility, compatibility (across browsers/devices/platforms), recovery (fault tolerance), and compliance. These testing types ensure broader quality aspects beyond just “does it work?”

Testing Methods: Manual vs Automated — Black Box, White Box, Gray Box

Testing can also be classified by how it's performed:

- White-Box Testing: Tests based on internal program logic and structure — requires internal code knowledge. Used often in unit or lower-level tests.

- Black-Box Testing: Tests based on inputs/outputs without knowledge of internal code — good for functional, acceptance, and system testing.

- Gray-Box Testing: Combines both — testers know some internal structure while focusing mainly on input/output behavior. Useful when you want a balance of internal insight and external behavior validation.

Automation is heavily favored for unit, integration, regression, and performance tests — because they can be run repeatedly and consistently. Manual testing still plays a role for exploratory, usability, and acceptance testing, especially when simulating real user behavior.

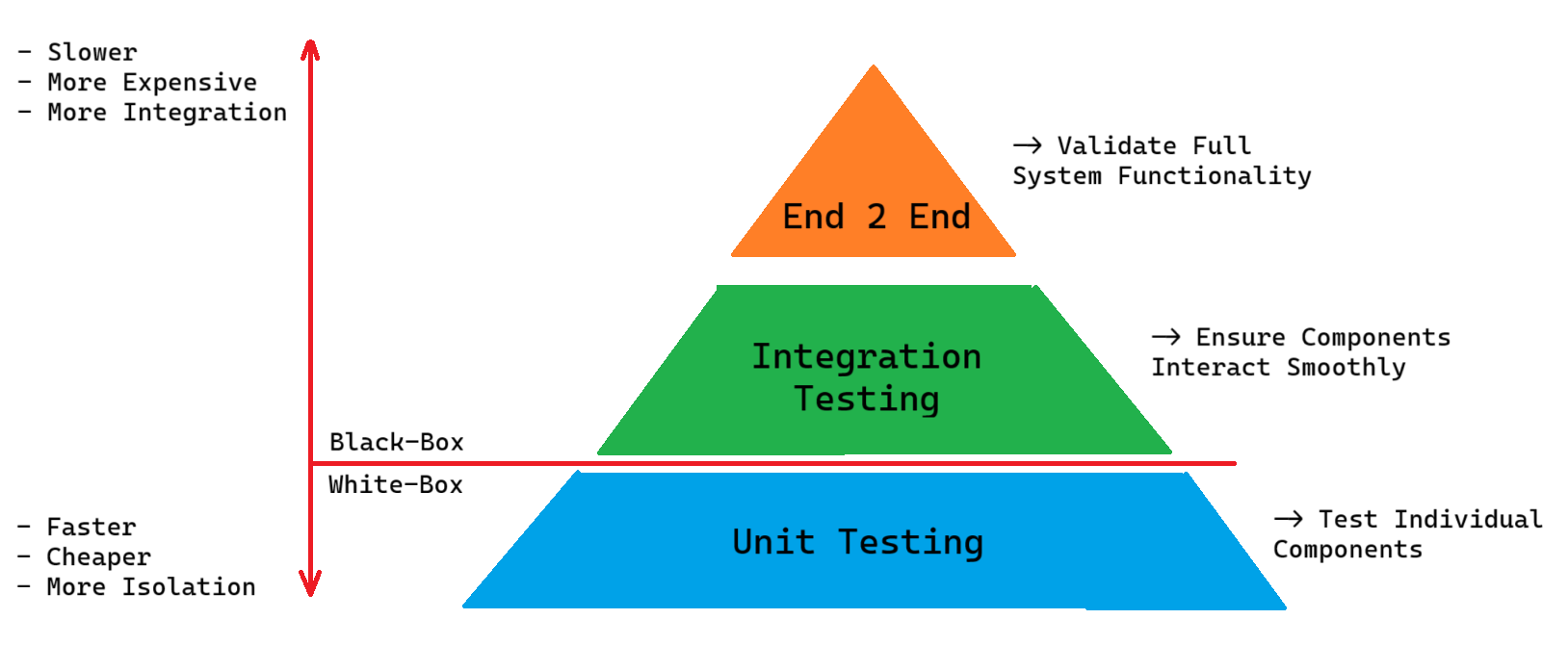

The Testing Pyramid: Why You Should Combine Tests

A common guiding philosophy is the Testing Pyramid: have many small, fast unit tests at the base; fewer integration tests in the middle; and even fewer full system or end-to-end tests at the top.

The idea: you catch basic defects early and cheaply (unit tests), verify module interactions (integration), and rely on a small number of high-value, broad-scope tests (system/E2E) — balancing coverage, speed, and maintenance effort.

This helps reduce regression risks and improves reliability while avoiding an explosion of slow, brittle end-to-end tests.

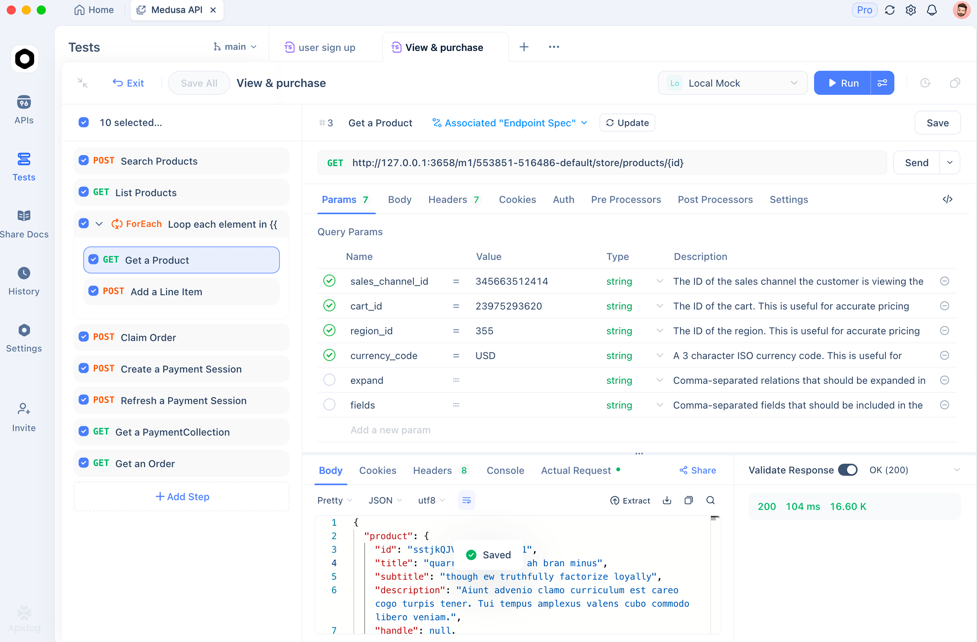

Testing APIs — Tools and Practical Advice

If your project offers APIs (REST, GraphQL, etc.), testing becomes especially important. You need to ensure endpoints behave correctly, responses match contracts, error handling works, and changes don’t break clients.

That’s where API-testing tools shine. For instance, Apidog — an API tool — helps you define endpoints, send test requests (GET, POST, etc.), inspect responses, check error handling, and validate logic — without manually writing all tests. Using such a tool, you can perform:

- Integration tests (test how frontend or services interact through APIs)

- Regression tests (re-run after changes to catch breaks)

- Contract or schema validation (ensure API spec remains consistent)

Combining traditional testing types (unit/integration/system) with API-specific testing dramatically improves confidence, especially for backend-heavy or service-oriented projects.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. Is it mandatory to use all types of testing for every project?

Not always. The testing strategy should match your project’s size, risk, and complexity. Small or short-lived apps might get by with unit and basic integration tests, while large or critical systems benefit from a full suite (unit → integration → system → performance/security).

Q2. What’s the main difference between unit testing and integration testing?

Unit testing checks individual components in isolation, without external dependencies. Integration testing verifies that multiple components or modules work correctly together (e.g. front-end ↔ API ↔ database) after integration.

Q3. When should I perform regression testing?

After any code change — new features, bug fixes, refactoring. Regression testing ensures existing functionality still works as expected, preventing “breaks” from creeping in.

Q4. What’s the advantage of automated testing vs manual testing?

Automated tests (unit, integration, regression, performance) are repeatable, fast, and less error-prone than manual tests. They scale well as code evolves. Manual testing remains useful for usability, exploratory, and user-experience aspects.

Q5. Can black-box testing catch all types of defects?

No — black-box testing focuses solely on inputs and outputs, without internal knowledge. It’s effective for functional or system-level behavior, but cannot guarantee internal coverage (like code branches, logic paths, or internal security issues) — for that, white-box or hybrid testing may be needed.

Conclusion

Understanding Types of Testing is vital for building reliable, maintainable software. By combining different testing types — unit, integration, system, performance, security, regression — you build layers of safety, catch defects early, and ensure software behavior remains correct over time.

For modern web apps or services, especially those exposing APIs, combining standard software testing practices with API-focused tools (such as Apidog) provides a strong foundation for quality, scalability, and smooth releases.

Ultimately, there is no one-size-fits-all testing strategy — but knowing your options, their trade-offs, and how to apply them will help you tailor a testing approach that fits your project, team, and goals.